Ⅰ. Introduction: From Case Dilemma to Institutional Reconstruction

In a commercial franchise contract dispute, the franchisor concealed the fact that the core technical patent was about to expire during negotiation, causing the franchisee to incur high franchise fees; after the contract took effect, the franchisor failed to provide agreed technical support, resulting in operational losses for the franchisee. If only liability for negligence in negotiation is pursued, the damages from the breach during performance cannot be covered; if only liability for breach of contract is recognized, the fraudulent fault during negotiation is overlooked. Such cases expose the limitations of traditional liability theory: when negotiation faults and performance defects coexist in the same contract, can we break through the “either-or” dichotomy and allow concurrent application of the two liabilities? This article reveals the jurisprudential logic and practical value of concurrent liability through normative deconstruction, comparative legal analysis, value justification, and practical pathways, providing a new paradigm for resolving complex contract disputes.

Ⅱ. Institutional Demarcation: Core Differences and Traditional Misunderstandings of Dual Liability

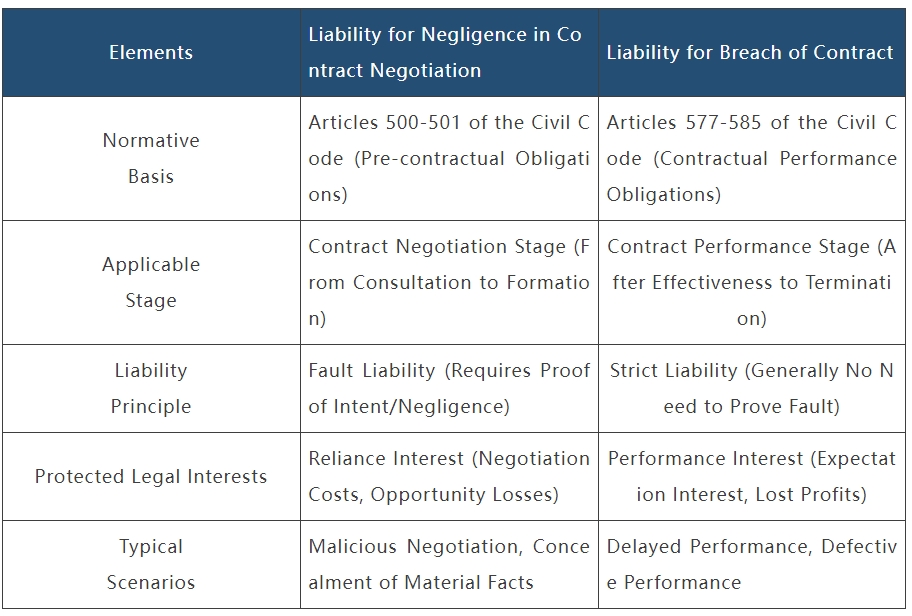

- The Two-Track Framework of Liability Systems

- Three Cognitive Misunderstandings in Traditional Theory

2. 1 Stage Segmentation Theory

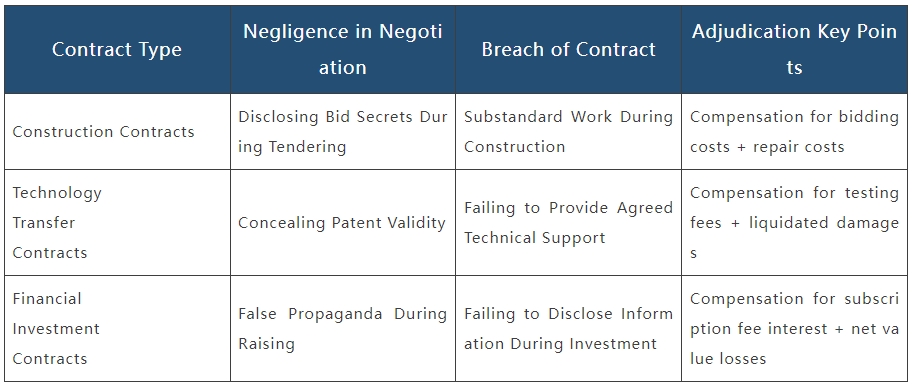

Mistakenly treating “formation” and “performance” as isolated stages, ignoring the continuity of transactions. For example, in a technology transfer contract, the assignor conceals patent defects during negotiation (negligence liability), and the defects lead to non-fulfillment of contractual purposes during performance (breach liability). These faults in different stages require separate evaluation.

2. 2 Legal Interest Substitution Theory

Confusing the essential differences between reliance interest and performance interest. The former aims to restore the state before negotiation (e.g., travel expenses for negotiation), while the latter aims to realize the state of complete contract performance (e.g., expected profits). These interests protect rights in different time-spaces and cannot substitute for each other.

2. 3 Normative Exclusion Theory

Mechanically interpreting Civil Code provisions and ignoring the normative space created by Article 500 for concurrent liability by removing the limitation of “contract not formed, invalid, or revoked”. In modern contract relations, “negotiation-formation-performance” is an organic whole requiring full-process liability regulation.

Ⅲ. Comparative Legal Insights: Institutional Consensus and Functional Evolution in Two Legal Systems

- Continental Law System: From Theoretical Creation to Legislative Confirmation

1. 1 German Law: The Birthplace of Negligence Liability and Concurrent Liability Theory

1. 1. 1 Paragraph 2, Article 311 of the German Civil Code clarifies that pre-contractual obligations apply to negotiation stages. Judicial practice allows concurrent liability for valid contracts through the “hypothetical faultless negotiation theory”. For example, if a seller conceals a defect during negotiation, the buyer can claim both negligence liability (compensation for price difference) and breach liability (warranty for defects).

1. 1. 2 Enlightenment: Breaking the traditional view that “no negligence liability for valid contracts” and establishing independent evaluation of faults in different stages.

- 2 Japanese Law: Judicial Precedent-Driven Liability Integration

1. 2. 1 Although the Japanese Civil Code does not explicitly provide for concurrent liability, “negligence in contract formation” precedents allow pursuing negotiation faults for valid contracts. For instance, a builder who fails to disclose geological risks during negotiation (causing extra foundation costs) and cuts corners during construction (requiring rework) may be held concurrently liable for both negligence and breach.

1. 2. 2 Enlightenment: Filling legislative gaps through judicial practice to comprehensively protect parties’ rights.

2. Common Law System: Functional Equivalence and Liability Coordination Mechanisms

2. 1 English Law: Cross-Application of Negligent Misrepresentation and Breach

2. 1. 1 Section 2 of the UK Misrepresentation Act 1967 allows claims for negligent misrepresentation during negotiation (reliance interest) while pursuing breach liability during performance. For example, an insurance broker who misassesses risks during negotiation and delays claims settlement after policy effectiveness may face concurrent liability claims.

2. 1. 2 Classic Case: White v. Jones established that a lawyer’s negligence causing will invalidity constitutes both breach of contract and tort liability, pioneering concurrent relief across liability types.

2. 2 American Law: Construction of a Two-Layer Protection System

2. 2. 1 Restatement (Second) of Contracts § 347 centers breach liability on expectation interest while protecting reliance interest during negotiation through “promissory estoppel”, forming a three-dimensional protection system of “pre-contract liability + contractual liability”.

3. Comparative Legal Consensus: Functional Convergence Despite Formal Differences

Both legal systems, whether through “normative legalization” in civil law or “judicial gradualism” in common law, exhibit two trends:

3. 1 Elastic Liability Boundaries: Shifting from strict stage division to full-process transaction protection;

3. 2 Composite Remedies: Allowing Overlapping accountability for faults in different stages to avoid legal evaluation gaps.

Ⅳ. Article 500 of the Civil Code: China’s Normative Breakthrough and System Value

- Legislative Evolution: From Limitation to Open System Reform

Article 500 of the Civil Code achieves two breakthroughs by removing the limitation of “contract not formed, invalid, or revoked” from the former Article 42 of the Contract Law:

Expanded Application Scope: Negligence liability now applies to valid contracts. For example, in a contract requiring administrative approval, one party concealing related-party transactions during negotiation (Item 2 of Article 500) and failing to apply for approval after effectiveness (Paragraph 2 of Article 502) may be respectively liable for negligence and breach.

Upgraded Obligation Types: The safety net clause of “other acts violating the principle of good faith” extends pre-contractual obligations to dynamic obligations such as loyalty and cooperation, providing a basis for fault determination in new transactions.

2. Normative Logic: Synergy with Breach Liability

2. 1 Liability Relay on the Time Axis:

2. 1. 1 Negligence liability regulates faithless acts during “negotiation-formation” (e.g., malicious negotiation, concealment);

2. 1. 2 Breach liability adjusts promise-breaking acts during “formation-performance” (e.g., delayed performance, defects).

2. 1. 3 Case Example: In a technology transfer contract, the assignor concealing patent examination status during negotiation (Article 500) and failing to perform due to patent invalidation after effectiveness (Article 577) may be ordered to compensate both due diligence fees (reliance interest) and transfer fees (performance interest).

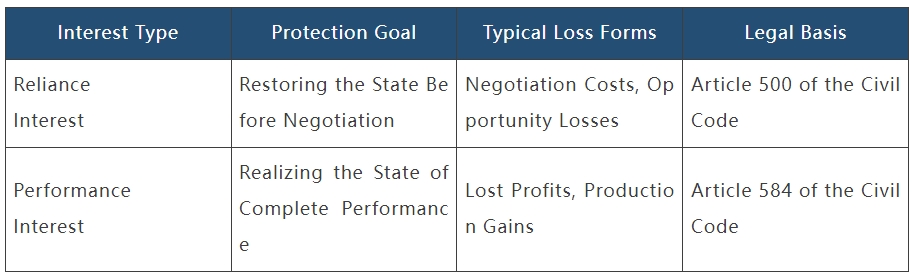

2. 2 Three-Dimensional Protection of Legal Interests:

2. 2.1 Reliance interest focuses on “the past”, repairing trust damages during negotiation;

2. 2. 2 Performance interest focuses on “the future”, ensuring contract expectations are met.

2. 2. 3 In financial disputes, a private fund manager concealing risks during negotiation (Article 500) and failing to disclose information during performance (Article 577) may be held concurrently liable to fully cover investors’ losses.

3. China’s Solution in a Comparative Legal Perspective

Through the open design of Article 500, Chinese law absorbs German theoretical essence and integrates local practices, forming a characteristic rule of “principle of concurrency + element limitations”. This echoes the “hypothetical faultless negotiation” in civil law and “negligent misrepresentation + breach” in common law, demonstrating institutional confidence and innovation.

Ⅴ. Value Justification: Three-Dimensional Rationality Reconstruction

1. Normative Logic: Full-Process Implementation of the Good Faith Principle

The principle of good faith established in Article 7 of the Civil Code manifests as a dynamic extension of obligations in contract relations:

During negotiation: Deriving pre-contractual obligations such as disclosure and confidentiality, breach of which triggers negligence liability;

During performance: Transforming into contractual obligations such as full performance and assistance, breach of which triggers liability for breach. These act as “time slices of good faith”, jointly constructing three-dimensional constraints on contractual behavior to prevent parties from evading liability through stage segmentation.

2. Legal Interest Protection: Incommensurability of Reliance and Performance Interests

The essential differences between the two interests determine the necessity of concurrent liability:

In equity investment practices, an investor concealing liabilities during negotiation (overpayment) and failing to inject capital during performance (project losses) may be separately liable for negligence and breach, clearly distinguishing between damages in different stages.

3. Economic Analysis: Institutional Choice for Minimizing Transaction Costs

Ex Ante Deterrence: Dual liability increases the expected cost of default, curbing strategic defaults like “malicious negotiation + careless performance”;

Ex Post Efficiency: Consolidating claims in a single lawsuit avoids repetitive litigation, conforming to the Civil Procedure Law’s joint litigation rules and reducing judicial resource consumption.

VI. Practical Pathways: Element Identification and Operational Guidelines

- Four-Element Identification Model for Concurrent Liability

Time-Space Element:

Negligence acts occur before contract formation or during effectiveness pendency (e.g., negotiation period, pending approval);

Breach acts occur after contract effectiveness and before termination (e.g., performance defaults).

Fault Element:

Faults in different stages are independent (e.g., negotiation fraud vs. performance delay belong to different obligation breaches);

Negligence requires proof of fault, while breach generally does not.

Causation Element:

Reliance losses directly result from negotiation faults; performance losses directly result from breach acts.

Loss Element:

Losses are clearly distinguishable with no overlap (demonstrable via “time-conduct-loss” comparison tables).

2. Typical Supported Scenarios in Judicial Practice

3. Litigation Strategies: Practical Points from Evidence to Defense

Plaintiff’s Burden of Proof:

Create visual aids (e.g., liability stage timelines, loss breakdown tables) to clearly present fault acts and corresponding damages in different stages;

Prioritize citing Articles 500 and 577 of the Civil Code, supplemented with Supreme People’s Court bulletin cases for persuasiveness.

Defense Against Defendant’s Objections:

Against “liability exclusion”: Stress that the law does not prohibit concurrency, and the two liabilities belong to different stages protecting distinct legal interests;

Against “duplicate compensation”: Prove through loss schedules that the two losses are independent with no overlap.

VII. Conclusion: Building a Full-Chain Contract Liability Protection System

From Jhering’s negligence liability theory to the Civil Code’s normative innovation, and from German theoretical creation to Chinese judicial exploration, the evolution of concurrent liability has always responded to transactional complexity. When negligence liability and breach liability form a protective synergy under the same contract, their significance lies not only in legal rule consistency but also in the full-process defense of market participants’ rights—holding faithless negotiators liable for reliance losses and promise-breakers liable for performance losses, ultimately achieving a market order of “trust in transactions, accountability for defaults”.

For legal practitioners, it is essential to break free from traditional liability theory through systematic thinking, accurately identify obligation breaches in different stages, and pursue maximum relief for clients through layered evidence and normative combinations. This is not just a legal technique but a practice of the Civil Code’s core spirit of “rights protection”. When every contract dispute is fairly evaluated within the framework of concurrent liability, contractual justice can truly become the cornerstone of the market economy.

This article solely reflects the author’s personal views and should not be regarded as formal legal advice or conclusions issued by BZW Law Firm or its lawyers. Should you wish to reproduce or quote any content from this article, please contact us via email. If you are interested in further exchanging views or discussing this topic, you are welcome to leave a message.